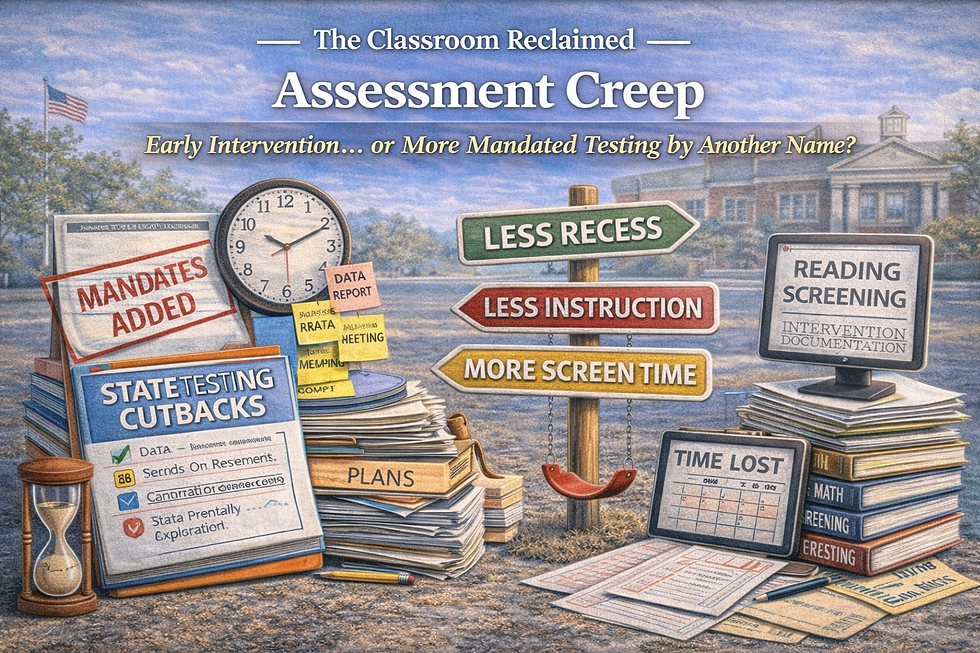

Assessment Creep

- Al Felder

- 29 minutes ago

- 5 min read

Early Intervention… or More Mandated Testing by Another Name?

One of the hardest realities in public education is this: the state almost never removes a mandate—it stacks a new one on top of the old one.

That’s why many educators are skeptical when lawmakers say, “We’re reducing testing.” Sometimes what they mean is, “We’re reducing one test,” while quietly adding several new required assessments and data cycles.

HB0002IN is a perfect example of why that skepticism exists.

In some places, the bill signals interest in reducing statewide standardized testing (through a federal waiver process). At the same time, it expands required screening and monitoring expectations—especially in the grades where schools already feel most burdened.

The result could be what many educators have lived through for years:

assessment creep—more testing windows, more reporting, more plans, more data meetings, and less time for instruction.

Let’s look at what’s being added and what it means for public schools.

What the bill does (plain English)

HB0002IN adds/expands required screening expectations in public education, including:

1) K–5 Math Screening (new)

Beginning in 2026–27, districts must administer a K–5 math screener at least three times per year. Students who fall below benchmark trigger additional steps—including an Individualized Math Plan (IMP) and targeted supports.

2) Grades 4–8 Reading Screening (new expansion)

HB0002IN requires an MDE-approved reading assessment system that includes a universal screener administered three times per year (beginning/middle/end), along with diagnostics and progress monitoring. Students identified as deficient trigger intervention steps and reading plans.

3) K–3 Reading Screeners (already in place)

Mississippi already requires K–3 universal screeners at least three times per year. HB0002IN doesn’t remove those; it adds layers on top of them.

In other words, even if the bill reduces some statewide summative testing in theory, it expands required screening cycles across multiple grade spans.

Why this is being proposed (the “sales pitch”)

Supporters usually argue:

Early identification prevents long-term failure

Screeners are short and targeted (not like long state tests)

Frequent screening helps teachers respond faster

Data-driven intervention is a better use of time than waiting for year-end scores

If you catch gaps early, you reduce later remediation and dropout risk

There’s truth here: early intervention matters, and good screening can help.

But the real question is not whether screeners can be useful. The question is:

What happens when screeners become mandates layered on top of everything else?

Potential upsides for public education

1) Earlier detection of struggling students

When implemented well, screening can:

Identify gaps before they grow

Trigger support sooner

Help teachers target instruction

Reduce “wait until the state test” delays

This is especially important in early math and reading, where foundational gaps snowball.

2) Better consistency across schools

If the system uses consistent tools and expectations, it can reduce the variation where:

One school screens well

Another screens inconsistently

Intervention depends on the principal

Support varies by zip code

Consistency can protect students—if it’s paired with real resources.

3) More actionable data than end-of-year test results

State summative scores often arrive after the year ends. Screeners, in theory, can provide data that teachers can act on quickly.

Potential downsides and unintended consequences

1) More testing windows mean less teaching time

Even “short” screeners require:

scheduling

administration

make-ups

staffing coverage

training

data uploads

and time to analyze results

Multiply that by three times per year across multiple grade bands, and districts lose a measurable amount of instructional time—especially in elementary schools.

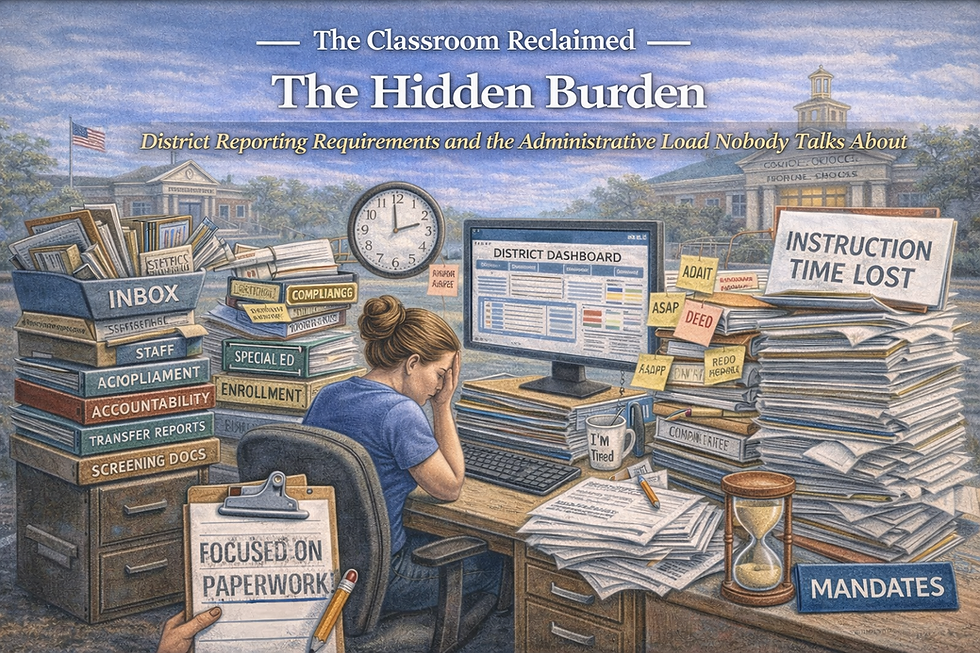

2) Screening mandates create paperwork mandates

Screeners are rarely just screeners. They trigger:

intervention plans

progress monitoring cycles

parent notifications

documentation requirements

data team meetings

and compliance checks

The hidden burden is not the screener itself. The hidden burden is what the screener requires afterward.

3) It can increase screen time in the grades that need less screen time

Many screening tools are computer-based.

That creates a values conflict for many educators and parents:

We say young children need movement, play, and hands-on learning

But we keep adding more screen-based assessment requirements

If policymakers truly believe movement-rich learning is important, assessment policy should align with that—not work against it.

4) Mandates without intervention capacity become “identification without help.”

This is the most damaging outcome.

If districts identify more needs through screening but do not receive:

intervention staff

tutoring support

math specialists

reading specialists

SPED staffing capacity

or time in the schedule

Then, screening becomes a system that labels students without meaningfully helping them. That increases frustration and decreases trust.

5) Schools can become data factories instead of learning communities

When compliance increases, the culture shifts:

Teachers feel watched

Principals become data managers

Instruction becomes pacing-driven

Students become numbers

Morale declines

Data should serve learning. When learning is used as data, the system breaks.

Who benefits most—and who is at risk?

Likely beneficiaries

Districts with strong intervention staffing and MTSS infrastructure

Schools with the time and personnel to respond quickly to screening results

Students whose needs are identified early and supported effectively

At-risk groups

Rural districts with limited intervention staff

Schools are already short on teachers and substitutes

Elementary students are losing movement and recess time

Teachers who carry the burden of plans and documentation without support

What districts should do now (practical steps)

1) Guard against “testing creep” in your calendar

If these mandates expand, districts must protect:

recess

movement breaks

science and social studies time

enrichment learning

teacher planning time

A calendar packed with assessments quietly squeezes out the very practices that improve learning.

2) Build streamlined MTSS routines that reduce paperwork

If plans are required, build:

consistent templates

manageable documentation expectations

clear decision rules

and systems that support teachers rather than bury them

3) Advocate for intervention funding, not just assessment requirements

Screening without staffing is ineffective. Districts should press the state for:

specialists

intervention positions

training

time in the schedule

and funding that matches expectations

4) Keep screening in its proper place

Screeners should inform instruction, not become the center of instruction.

Questions policymakers should answer publicly

If lawmakers want early intervention without crushing schools, they should answer:

How much instructional time will be lost to expanded screening cycles?

What funding is provided for intervention staffing and materials?

How will districts avoid excessive computer-based testing in early grades?

What safeguards prevent these mandates from reducing recess and hands-on learning?

If the state wants less testing, why is it adding more required assessment windows?

A balanced takeaway

Early identification and intervention can be a good policy.

But when screening becomes a mandate layered onto an already burdened system, it turns into assessment creep—more required cycles, more compliance, and less time for the kind of teaching and learning that actually works.

The goal should be simple:

Test less. Teach more. Intervene earlier—with real support—not just more data.

Reflection question for readers

If a district identifies more struggling students through new screeners, will the state provide the staffing and time to help them, or will schools be left with more labels and less capacity?

Comments