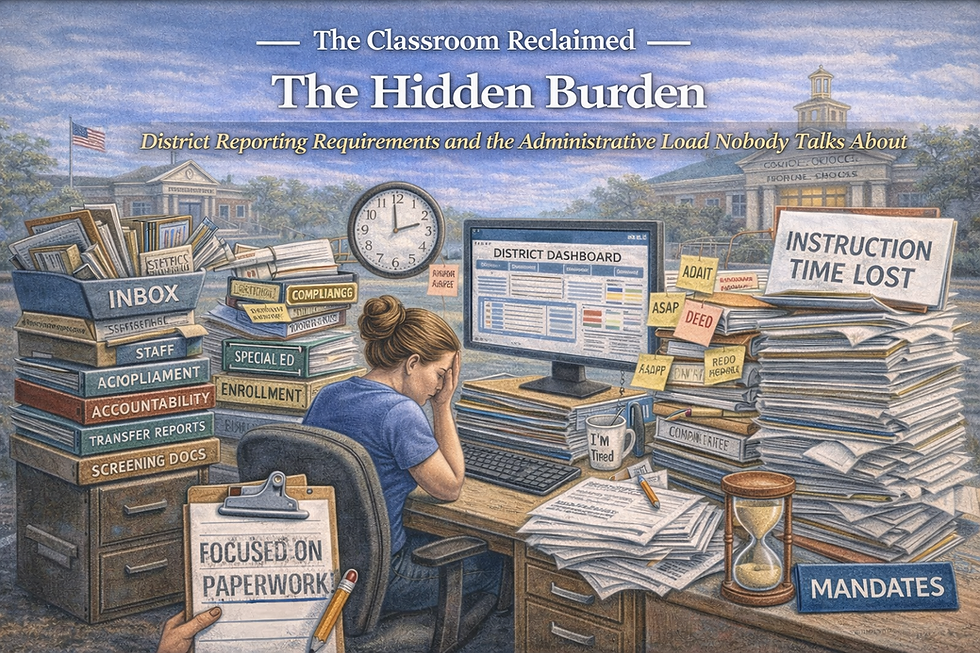

The Hidden Burden

- Al Felder

- 13 minutes ago

- 4 min read

District Reporting Requirements and the Administrative Load Nobody Talks About

When people debate education policy, they usually focus on the biggest headlines: school choice, testing, accountability grades, teacher pay, or safety.

But the daily reality of public education often lives in the quiet, invisible work that keeps the system running:

reporting.

Not the kind of reporting that improves teaching. The kind that demands:

new dashboards

new data submissions

new compliance checks

new documentation trails

new public-facing reports

and new deadlines layered on top of the old ones

HB0002IN contains several provisions that expand transparency and tracking. On paper, that can sound reasonable—even helpful. In practice, it can create a serious problem for public schools:

Administrative load grows faster than instructional capacity.

And when that happens, schools don’t become more accountable. They become more exhausted.

Let’s talk about the good and the bad.

What “administrative load” actually means in a district

When lawmakers add a reporting requirement, it rarely affects one person. It triggers a chain reaction:

someone must collect the data

someone must verify it

someone must upload it

someone must correct errors

someone must write policies around it

someone must answer questions from parents, media, and stakeholders

someone must train staff to follow new procedures

someone must document proof for audits and disputes

This is the hidden truth: reporting is not a single task. It becomes a system.

And systems require time, staffing, and coordination.

Why HB0002IN-style reporting requirements sound good (and sometimes are)

There’s a fair argument for transparency:

1) Transparency can build trust

Public schools operate with public dollars. People deserve to understand:

how money is spent

what outcomes look like

what enrollment patterns are happening

what safety policies are in place

When transparency is clear and contextualized, it can strengthen community confidence.

2) Standardized reporting can reduce confusion

When each district reports differently, the public gets mixed messages. A standardized format can reduce:

inconsistent data definitions

rumors and misinformation

“apples-to-oranges” comparisons

3) Better data can help districts improve internally

Some reporting requirements can actually help leaders identify:

staffing gaps

intervention needs

attendance trends

budget pressures

program effectiveness

In that sense, data can serve to improve.

But only when the system is designed to support improvement—not drown schools in compliance.

The problem: reporting is expanding while district capacity is not

Public schools are already operating under:

federal reporting (special education, Title programs, accountability)

state reporting (testing, attendance, finance, discipline, staffing)

local reporting (board reporting, audits, parent communication)

HB0002IN adds additional layers in multiple areas—financial transparency, enrollment/transfer reporting, screening documentation, accountability dashboards, and more.

Even if you support the goals, the burden is still real:

Districts don’t get a new staff position every time the state adds a new requirement.

So the same people carry more weight.

Five ways expanded reporting can harm public education

1) It pulls leadership away from instruction

When central office staff become compliance managers, they spend less time on:

coaching principals

supporting teachers

strengthening curriculum

improving intervention systems

solving real problems at the campus level

Compliance doesn’t teach a child. People do.

2) It creates “paper accountability” instead of real accountability

A district can look “compliant” while still struggling to meet student needs.

Reporting can become a substitute for improvement:

“We filed the report.”

“We posted the dashboard.”

“We completed the plan.”

But a completed plan does not equal a changed classroom.

3) It increases stress on frontline staff

The public usually thinks reporting is done by “the district.”

In reality, reporting often lands on:

principals

counselors

testing coordinators

interventionists

secretaries

teachers who now have more documentation responsibilities

Those are the same roles already stretched thin.

4) It makes districts more vulnerable to misinformation

Public reporting without context can backfire.

When people see numbers without understanding:

poverty

mobility

SPED needs

rural transportation costs

staffing shortages

aging facilities

They often assume incompetence or waste.

That fuels distrust—not improvement.

5) It makes the system less attractive to work in

Here’s the long-term consequence:

The more compliance-heavy a system becomes, the harder it is to recruit and retain good people.

Teachers don’t want to teach in a system where:

paperwork is endless

data meetings never end

mandates keep growing

and the public assumes the worst

If lawmakers keep adding burdens to public schools while loosening burdens elsewhere, the public system becomes the place no one wants to be.

And that is how public education erodes—not overnight, but over time.

The big question: if the state wants transparency, will it fund capacity?

If lawmakers truly want expanded reporting, they should be honest about what it requires:

modern data systems

training

time

personnel

and funding

Without that, reporting becomes an unfunded mandate—and public schools pay for it with instructional time and staff burnout.

What a smarter transparency policy would look like

If the goal is transparency without harm, the state should follow a few principles:

1) Remove old requirements when new ones are added

If a new dashboard is required, eliminate redundant reports.

Don’t stack. Streamline.

2) Build “context” into public reporting

Numbers without explanation create mistrust. Every dashboard should include context indicators such as:

mobility rates

poverty measures

staffing vacancy rates

SPED intensity

transportation miles

facility age

That doesn’t excuse results—it makes results understandable.

3) Fund the work

If the state mandates frequent reporting, it should support:

data staffing

training

system upgrades

and district's capacity to do it accurately

4) Focus reporting on what families actually need

Parents want clarity, not spreadsheets:

Is my child learning?

Is the school safe?

How can I help?

What support is available?

Transparency should serve families—not overwhelm them.

A balanced takeaway

Transparency is not the enemy of public education.

But unfunded transparency mandates can quietly weaken public education by draining time, energy, and staffing away from instruction.

Public schools need fewer layers of paperwork and more support for what actually moves learning:

stable staffing

strong teaching

effective intervention

healthy school culture

and meaningful learning time for kids

If lawmakers want real accountability, they should reduce the burden on the people doing the work—not add another report to the pile.

Reflection question for readers

If a new reporting requirement takes time away from teaching and intervention, is it really improving education—or just increasing paperwork?

Comments