Who Serves Every Child?

- Al Felder

- 41 minutes ago

- 5 min read

The Public School Obligation in a Choice-Driven System

In school choice debates, we hear a lot about options, innovation, freedom, and competition.

What we hear far less about is obligation.

Because while policy conversations often center on who gets to choose, public education still centers on who must serve. And in Mississippi—as in most states—public schools remain the institutions legally and practically responsible for educating every child who walks through the door.

That includes children who arrive late, leave mid-year, return after disruption, need intensive services, require transportation, or bring complex academic and behavioral needs.

As choice expands under HB0002IN, this basic truth becomes more important, not less:

Public schools are still the universal provider.

If policy does not account for that responsibility, “choice” can become less about improving education and more about redistributing burdens.

The distinction we can’t ignore: access vs obligation

Let’s define the difference clearly.

Access

Families can access educational options under state policy pathways.

Obligation

Public schools are obligated to:

enroll resident students (including mid-year entrants),

provide required services under federal and state law,

maintain staffing and infrastructure to serve broad student needs,

and continue operating even when mobility and funding volatility increase.

In short, choice systems may expand access, but public schools retain a universal duty.

That duty has real operational, financial, and human costs.

What does “serve every child” mean in practice

When people hear “public schools serve everyone,” it can sound like a slogan. In district life, it is a daily reality.

Public schools serve:

students with significant disabilities requiring specialized supports,

students in poverty who need layered interventions,

students experiencing homelessness or unstable housing,

students entering from other systems mid-semester,

students with interrupted learning histories,

students with discipline and trauma-related needs,

students needing transportation across wide geographic routes,

students requiring meals, counseling, and wraparound supports.

This is not optional work. It is mandated work—and morally necessary work.

And it is one reason why apples-to-apples comparisons between systems often miss the point.

Why choice expansion can concentrate responsibility in public schools

As options expand, student movement rarely occurs evenly. It can be selective and patterned. Over time, public schools may become more concentrated with students who:

have fewer family-level resources to navigate options,

require more specialized services,

move more frequently,

and need the most stability from their school system.

That doesn’t mean families are doing anything wrong. Families make the best decisions they can with the information and circumstances they have.

But policy must recognize the downstream effect:

If one system remains universally obligated while others operate with narrower service burdens, the universal system becomes increasingly complex without proportional relief.

The fairness question: can we compare outcomes without comparing obligations?

A common political narrative is:

“If schools are good, families will stay. If not, they won’t.”

There is some truth there. Public trust matters. School quality matters.

But this narrative becomes incomplete when it ignores different obligations.

You cannot fairly compare systems if:

one must take all students at any time,

one must run transportation for everyone eligible,

one must maintain a broad special education capacity,

one must meet extensive reporting and compliance duties,

and another operates under a narrower set of legal and operational burdens.

That’s not an argument against choice. It’s an argument for honest comparison.

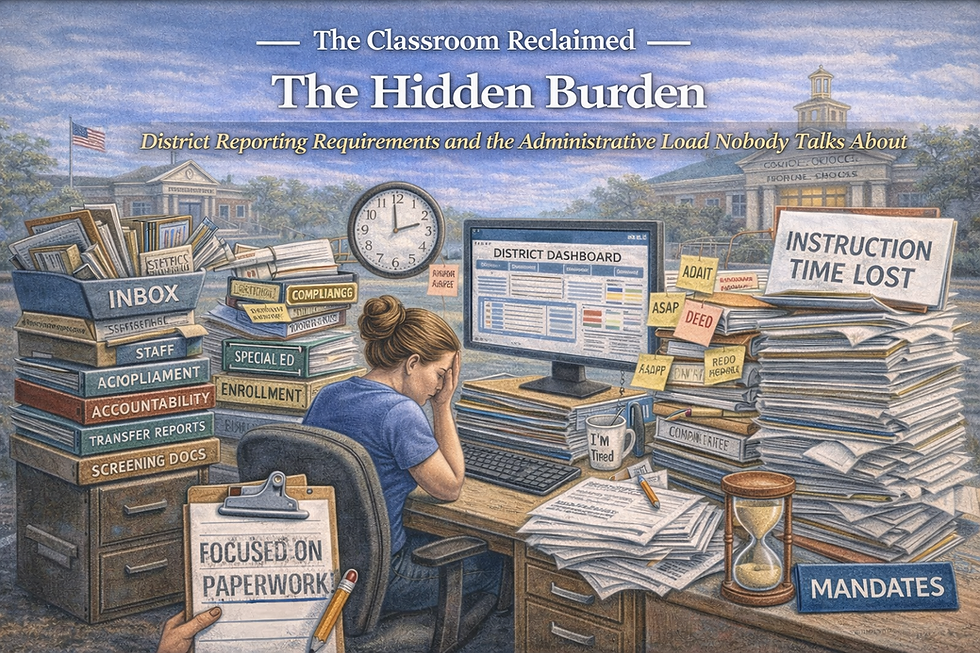

Where this hits hardest: staffing, services, and morale

When public schools carry universal obligations under increasing strain, the pressure shows up in predictable places.

1) Staffing pressure

Schools need more specialized roles, but budgets tighten as enrollment shifts unpredictably.

2) Service pressure

Interventions, counseling, SPED coordination, and behavior supports face rising demand with limited capacity.

3) Schedule pressure

As needs rise, leaders spend more time triaging and less time on proactive improvement.

4) Morale pressure

Educators feel blamed for outcomes while carrying the most complex student realities under the most mandates.

If policy keeps adding asymmetry, the workforce impact becomes long-term: recruitment gets harder, retention weakens, and institutional knowledge drains away.

To be fair: what choice supporters are right about

A balanced view should acknowledge that choice advocates are not always wrong. They are right that:

families want agency,

public systems should be responsive,

complacency should never be protected,

and schools should earn trust continuously.

Those are valid points.

But responsiveness and fairness are not opposites. You can support family options and protect the universal provider that serves every child.

Good policy should do both.

What a fair framework would include

If Mississippi wants a durable, ethical education framework in a choice-driven environment, policymakers should build around shared responsibility.

1) Transparent obligation reporting across systems

If outcomes are compared, obligations should be visible too:

mobility rates,

service intensity,

mid-year intake load,

transportation burden,

and high-need student concentration.

2) Comparable student protections

Public funding should come with clear safeguards and service expectations that consistently protect students.

3) Stability funding for universal-service districts

Districts with universal obligations need funding models that account for fixed costs and high-need concentrations.

4) Accountability that includes contribution, not just scores

Systems should be evaluated not only on outcomes, but also on who they serve and how consistently they serve them.

5) Policy language that names public schools’ civic role

Public schools are not one option among many in a purely private market. They are the civic backbone that keeps the community open and ready for everyone.

What district leaders can do now

Even within policy uncertainty, district leaders can take proactive steps.

1) Document your obligation footprint

Track and communicate:

mid-year enrollment inflow,

high-needs service demand,

mobility trends,

transportation complexity,

and intervention intensity.

2) Tell the operational story with clarity

Communities often see outcomes but not inputs. Explain what universal service requires day to day.

3) Protect frontline capacity

Prioritize staffing and structures that keep high-need support stable, even under budget pressure.

4) Advocate with data and principle

Frame public education not as a competitor asking for favors, but as a constitutional and civic institution carrying non-negotiable obligations.

A balanced takeaway

School choice conversations often begin with freedom. They should also include responsibility.

Public schools still serve every child—especially the children who arrive with the greatest needs and the fewest advantages. That obligation is the moral center of public education and the practical backbone of communities.

If policy expands choice without protecting the universal-service mission, it doesn’t create a stronger system. It creates a fragmented one, where burdens concentrate in the very schools we still rely on to serve all.

The future of education should not be built on who can opt out of obligation. It should be built on how we share it fairly.

Reflection question for readers

If public schools remain responsible for serving every child, should policy require all publicly funded options to share more of that responsibility—or should one system continue carrying most of it alone?

Comments